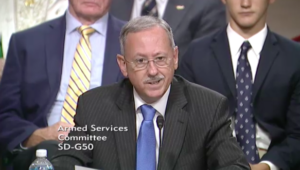

WASHINGTON: A Pentagon study on how to counter counter hypersonic missiles – which China, Russia, and the US are all developing – is in final review and will be out soon, the director of the Missile Defense Agency said today. The Analysis Of Alternatives (AOA) looks at both existing interceptors and new designs, as well as directed energy weapons such as lasers, Lt. Gen. Samuel Greaves said at the Center for Strategic & International Studies this afternoon.

Countering hypersonics is a high priority, but hardly the only one, in the administration’s recently concluded Missile Defense Review, which says increasingly dangerous and diverse threats will require the US to develop both new defenses and new offensive weapons. It’s an approach that holds up well now that the administration is withdrawing from the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty after years of Russian violations, the deputy undersecretary for policy, David Trachtenberg, said at CSIS.

Stopping Hypersonics And Streamlining Acquisition

Hypersonic missiles could slip through current defenses because they fly much faster than traditional cruise missiles but much lower and more maneuverably than ballistic missiles. So, the Missile Defense Agency director said, “the agency, with the department, has completed an Analysis Of Alternatives looking at hypersonic defense.”

“Fast interceptors… are one option, directed energy is another, and there are some other options in there,” Greaves elaborated. “It’s essentially assessing the current suite of available interceptors to see if they’re fast enough to get to the target and win the tail chase…. We have worked with industry to assess available interceptors as well as potentially new interceptors to execute that mission.”

“I cannot say today that definitively we need a new interceptor. I will await the results of the analysis of alternatives,” Greaves emphasized. “That AOA is now in final coordination and review within the department and should be released soon.”

Greaves is being cautious here, but given that his own experts helped write the report, he probably both knows and agrees with whatever it recommends — he just can’t say publicly what that is before his bosses have signed off.

When that recommendation does come out, it’ll be up to MDA to execute it as the Defense Department’s lead agency for countering hypersonics. It’s the kind of high-tech, high-stakes, high-risk work the agency was created for. MDA’s unique legal authorities and funding let it bypass much of the usual acquisition bureaucracy – but critics have argued that just lets the agency “rush to failure” by fielding inadequately tested technologies. So should MDA be brought under the standard DoD 5000 regulations?

“I absolutely oppose that. It’s wrong,” Greaves said bluntly. “I spent quite a bit of time in the Air Force” – in the regular acquisition bureaucracy – “underneath the 5000 principles and processes. I’ve spent time equally in the National Reconnaissance Office and the Missile Defense Agency,” which both have exemptions from that process. “Having qualified people in responsible positions with the authority to make those decisions, that is the secret sauce,” he said.

Ending INF But Not Deploying Nukes

The big news of the day on arms control was the administration’s formal announcement that it will withdraw from the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty, starting tomorrow. But undersecretary Trachtenberg argued that the end of the landmark 1987 accord doesn’t require any revisions to the Missile Defense Review: To the contrary, he argued, it vindicates it.

“I don’t think the demise of the INF treaty really affects the approach that we’ve taken in the MDR at all, because the MDR’s presumption is we need to defend against a growing proliferation of missile threats, period,” Trachtenberg said.

“The demise of the INF treaty — let’s be clear about this — is because the Russians have violated it and repeatedly violated it for years…. That is indicative of part of the problem [that is] captured in the MDR.”

In particular, the review puts a new emphasis on cruise missiles, not just ballistic missiles. (Cruise missiles fly low and slow through the atmosphere, but can maneuver; ballistic missiles fly at blinding speeds but in predictable trajectories, much of the time through space). Hence the name Missile Defense Review, as opposed to previous administrations’ Ballistic Missile Defense Reviews. The Russian weapon that allegedly violates INF, the Novator, is a cruise missile.

Withdrawing from the treaty means the US can legally build INF-banned weapons of its own: ground-launched missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 km. (That’s 310 to 3,417 miles, a range band chosen because of the peculiar geopolitics of the Cold War in Europe). But skeptics point out any such weapons would have to be based on the soil of European allies, many of whose citizens protested bitterly the last time the US tried such a move, back before the INF accord was signed.

Trachtenberg dismisses the comparison. The controversial Pershing ballistic missiles and Ground-Launched Cruise Missiles (GLCMs) of the 1980s were nuclear weapons, but the new ones will be precision-guided conventional weapons.

Deploying new nukes to Europe, “we have no plans to do that,” Trachtenberg emphasized. “What we have been planning to do and have been doing is …research and development of conventionally armed systems within the range that is currently banned by the treaty.”

The US Army, in particular, sees such long-ranged (but not intercontinental) precision-guided weapons as vital tools to take apart high-tech defenses, especially anti-aircraft weapons, radars, and air defense command posts that would otherwise keep American airpower at bay. The INF Treaty bans such systems almost as an afterthought — conventional long-range missiles were irrelevant at the time because, before precision guidance, it took a nuclear warhead to guarantee a hit on a target hundreds of miles away — but they have become increasingly central to a new era of warfare.

Navy jet trainer fleet operations remain paused after engine mishap

One week after the incident, a Navy spokesperson says the service is continuing to assess the fleet’s ability to safely resume flight.