WASHINGTON: The Pentagon’s pushing hard on hypersonics. There’s $2.6 billion in the 2020 budget for R&D. The services are sharing technology and flight test data. But what the military does not want is a massive multi-service program like the F-35.

[Click here to read all our 2020 budget coverage]

“It’s a joint interest program, not a joint program,” Army undersecretary Ryan McCarthy told reporters this morning on the sidelines of the McAleese/Credit Suisse conference here. “We don’t want a big kind of program office like you had for” — he paused — “other major defense acquisition programs.”

“We share office space,” McCarthy said. “We will learn from each other’s tests, [and] we will potentially buy components together, [but] not either slow each other down or tweak the requirements.”

“The deployment of the weapons system is fundamentally different, and we respect that,” McCarthy said: The Army needs to launch its hypersonic weapons from trucks and tracked vehicles, the Air Force from jets, the Navy from aircraft, surface ships, and submarines. While the services are eager to share the costs of developing new technologies and to buy common components where they can, he said, none of them wants to have to compromise its unique requirements — the official to-do list of how the weapon has to work — to produce a single weapon all three can use.

(Interestingly, the massive Future Vertical Lift initiative — now split into at least two separate Army programs, the FARA scout and the FLRAA transport — went through this “let’s not be like F-35 stage” almost five years ago).

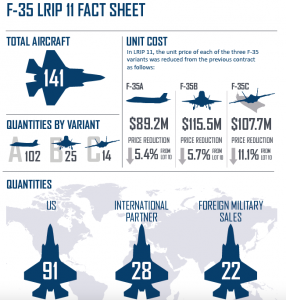

Yes, the F-35 Joint Program Office did produce three different variants: the Air Force’s F-35A can only operate off runways, the Navy’s F-35C can also fly from aircraft carriers, and the Marines’ F-35B can even take off and land vertically on helipads and highways. But enough key components were shared that what one service wanted often impacted the others, adding complexity or cost for features they didn’t want..

For hypersonics, by contrast, the Defense Department is trying “about half a dozen” independent programs across the services and DARPA, said Mike White, the Pentagon’s assistant director for hypersonics. The exact number, he told reporters yesterday, depends on how strictly you define “hypersonic” — literally, it just means moving through the air Mach 5-plus — and whether you clump smaller contracts together or count them separately.

Six Missiles, A Little Defense, & Some History

White didn’t provide a list, but based on our own research, we’d tentatively identify six, though designations keep changing and some of these programs may be different names for the same thing or spin-offs of common ancestors:

- Navy: Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS).

- Army: Land-Based Hypersonic Missile.

- Air Force: Hypersonic Conventional Strike Weapon (HCSW) and Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW) — both, incidentally, Lockheed Martin products, like the F-35.

- DARPA & Air Force: Tactical Boost-Glide (TBG) and Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC).

Note these are all offensive hypersonic missiles. Defense against hypersonic missiles, which is much harder and probably requires new tracking satellites, is currently the job of the Missile Defense Agency. MDA is only getting $157 million for that purpose in 2020 — less than a sixteenth of the offensive funding — but White said defense is laying the technological foundations and is “not very far behind” offense. In third place, he said, is reusable hypersonics: not missiles, which fly one way, once, but actual hypersonic aircraft, manned or unmanned.

White’s spent four decades researching hypersonics and other missile technology, and three months ago he became the chief hypersonics coordinator for the chief fan of hypersonics, Undersecretary for Research & Engineering Mike Griffin. In that role, White said, he handles “vision,” “strategy,” and “integration” of the different programs — but he doesn’t own them. They’re owned by the services, which signed a Memorandum Of Agreement coordinating their efforts last spring.

White said he hasn’t seen any resistance from the services to overall DoD direction, only “an unprecedented among of collaboration.”

“We have multiple programs sharing a common booster, for example,” White said, but with “different hypersonic front ends.” Three of the programs, he added, derive from the Navy-led Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS), which in turn evolved from the Army’s Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW), which itself evolved from Sandia National Laboratory’s Sandia Winged Energetic Reentry Vehicle Experiment (SWERVE).

CPS had its first test flight in 2017 and will have another “in about a year,” White said. Across all the programs, “you will see a dramatic increase in the number of flight tests we conduct over the next several years,” which will require a corresponding ramp-up in the nationwide testing infrastructure.

How much? The current five-year spending figure for hypersonics across the Future Year Defense Plan (FYDP) is $10.5 billion, but that’s clearly a placeholder. ($10.5 billion divided by five years gives an average of only $2.1 billion, which makes no sense when this year, the first year, is already $2.6 billion and that figure is only going to go up). Plus Congress may plus-up funding well above the request, as it did last year, when it increased hypersonics to a total of $2.4 billion.

A big source of uncertainty: We’re still experimenting. “Right now…. there are not acquisition programs of record,” White cautioned. “Those programs are flight demonstration prototype programs and weapons systems prototype programs.” The decision to start a formal acquisition program of record, he said, is still “a number of years” away.

The ultimate goal? “A family of systems,” White said, “[using] air, sea, and land launch, that can handle both medium ranges and more intermediate ranges — think coastal attack and deep inland attack.”

Approximate ranges in miles from Chinese territory to select US and allied targets. SOURCE: Google Maps (Click to expand)

(White didn’t explain his terms, but this is presumably from the perspective of US forces firing from the sea or island bases at an opponent on the mainland of Eurasia, like Russia or China: Shorter-range weapons can only hit the coast, longer-ranger ones can go “deep inland.” The reference to “intermediate” ranges suggests somewhere between 500 and 5,500 km, the ranges covered by the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty from which the administration is now withdrawing).

White wouldn’t get more specific about ranges, understandably, except to say “it’s not intercontinental.” That’s significant, because previous efforts on what was called Prompt Global Strike were scuppered by fears that a sufficiently fast and long-range conventional missile would be mistaken for a nuclear ICBM, potentially triggering a nuclear war. (Even the original Navy/Air Force concept to break through China’s layered defense, AirSea Battle, faced deep concerns about how strikes on the Chinese mainland might escalate).

But that previous program envisioned weapons with ICBM-like ranges and flight paths, White said, firing from ICBM launch sites. In fact, one candidate was simply a Navy Trident ballistic missile with the nuclear warhead replaced by a conventional one.

Today’s hypersonics programs, however, will have shorter ranges and different flight paths. They’ll also be unique systems that were developed solely to carry conventional warheads, without a nuclear variant. Said White: “Any adversary who’s got the capability to detect [them] will quickly understand the difference.”

[Click here to read all our 2020 budget coverage]

In a ‘world first,’ DARPA project demonstrates AI dogfighting in real jet

“The potential for machine learning in aviation, whether military or civil, is enormous,” said Air Force Col. James Valpiani. “And these fundamental questions of how do we do it, how do we do it safely, how do we train them, are the questions that we are trying to get after.”