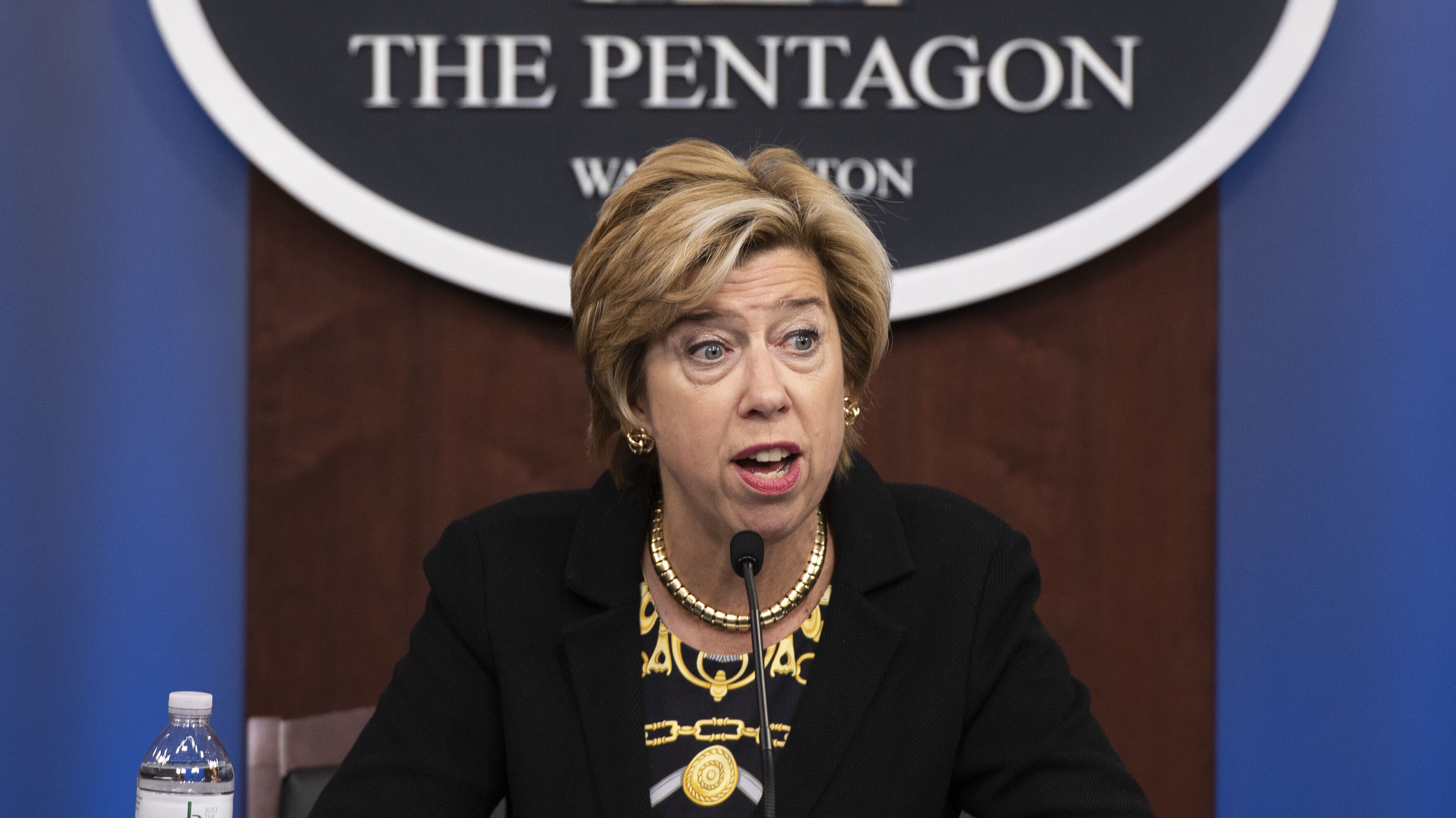

Since Ellen Lord left the Pentagon in January, there has been no confirmed A&S head. (DVIDS)

When Ellen Lord exited the Pentagon in January, she left plenty of major acquisition issues for her successor. But that person hasn’t appeared; after an aborted nomination of Mike Brown for the role, the Biden administration has yet to nominate anyone for the key acquisition & sustainment job. As a result, says former Pentagon official Jeff Bialos, it’s time to take a new approach to getting acquisition reform done in the building.

With the Pentagon all but guaranteed to go more than a full year without a confirmed undersecretary for acquisition and sustainment (A&S), it’s time for the Defense Department to consider cutting bait on another round of shiny new acquisition reforms. The new A&S, with less than three years at the helm, should adopt a policy of acquisition “triage,” and focus on producing specific acquisition outcomes that can meet our national security needs in a reasonable — as fast as possible — time frame.

Congress and DoD have attempted all nature of systemic reforms in recent years to address longstanding challenges of speed, cost and performance on defense programs, including: the dramatic splitting of the acquisition, technology & logistics office into the undersecretaries for A&S and research and engineering; encouraging the use of more flexible contract arrangements and collaborative approaches (like other transactional authority and consortiums); encouraging more and more rapid prototypes to spur innovation; building pilot projects like the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) to build bridges to Silicon Valley and remove barriers to entry; changing the incentives facing DoD acquisition executives; and implementing an Adaptive Acquisition Framework and yet again rewriting the 5000 series of regulations.

The reality, however, is that most of these efforts at institutional reform or reform by example have either fell short or only produced useful acquisition outcomes at the margin to date — that have not moved the needle on overall systemic shortcomings. While, by all accounts, more defense innovation has been unleashed in recent years, it remains uncertain whether any of it has or will be fielded or make a difference. And in some cases, we don’t know yet if these efforts will bear fruit.

Thus, rather than add to this list and promulgate yet another administration’s new acquisition reforms that will take years to bear fruit, its vital that the new DoD acquisition team turn to the challenges of realigning our acquisition outcomes with our national security needs and achieving acquisition accountability through improved system outcomes sooner rather than later — and to do so hand in hand with the military services in order to avoid stovepipes being created.

Ensure that acquisition programs are aligned with threat-and capability-based priorities. While some of these efforts are underway, it is important to conduct a top level review, together with the Joint Chiefs and services, of the order of battle against both high intensity threats from near peer competitors (China, Russia and the like) as well as the range of low intensity threats faced in recent years, from terrorism to insurgency to humanitarian relief to stabilization. While there is a broad consensus on the need to step up our “near peer” game and the bloom is off the rose of some of our lower intensity efforts (i.e., there is no appetite for Afghanistan-type engagements), we need to ensure we have the appropriate capabilities across this spectrum. While we need to deter and defend against high intensity engagements, we still are likely to meet in practice a range of low intensity threats in the years to come. In that context, we need to evaluate “alignment” — whether our existing acquisition programs are aligned with our national security needs — and make adjustments as warranted.

Launch accountability reviews to address major program and contractor specific performance issues. The future A&S head should conduct a focused review of the major acquisition programs to address serious performance problems (cost, duration and technical performance) and determine whether to redesignate certain programs as ACAT 1 (d) programs as appropriate. Separately, the A&S should, as it has at times in the past, conduct a review of the select programs of the major defense contractors quarterly to identify contractor-specific issues that cross-cut programs. Accountability should be the focus not only for DoD but for our contractor community.

Conduct a DoD-level, enterprise review of status of major investments in select critical technology areas to assess whether to they should be “pulled through” into new or existing programs of record. Nary a day goes by that we don’t hear that we are behind, have experienced a “near Sputnik” moment,” or are losing our advantage in technologies like artificial intelligence or hypersonics. Therefore, it is high time the department assess with disciplined metrics, on an enterprise wide basis (i.e., above the program level and bringing our R&E and A&S offices together) for each such critical technology, where we are on the development and maturation of these technologies, including their technology readiness levels; whether they are ripe for insertion into programs of record; and what steps should be taken to further develop, exploit, and integrate these technologies into the force (including eliminating duplication and overlap between programs, combining efforts where relevant, and so forth). While there often are legitimate reasons not to integrate such technologies into ongoing programs or fielded capabilities in the near term, the reality is that it is important to have senior officials — who do not face the day-to-day program budgets, deadlines and other parameters incentivizing short term thinking — to review and make some top level “pull through” judgments to get such technologies, where warranted, across the proverbial valley of death.

Review efforts to bring commercial innovation into DoD. From DIU to consortia to increased use of OTAs, there have been numerous efforts to ingest and inject new and emerging commercial technology into the DoD ecosystem. It’s now time to evaluate the status of these efforts, determine whether they are sustainable and valuable, and invest as warranted going forward. The review should address questions of whether such innovation efforts are being hindered with the rising use of traditional FAR provisions in OTAs and limitations on available funding on prototypes.

Enhance international collaboration with close allies. One of the hallmarks of the post-Cold War US defense strategy has been our willingness to work closely and collaboratively with allies and bring foreign innovation into the force. Unfortunately, one side effect of the recent focus on near-peer competition is that we have tended to create greater walls to accessing such innovation from abroad. We therefore need to identify ways to work more closely on concrete programs and investment opportunities with allies to bring promising new foreign technologies and capabilities into the US force and the innovation and affordability that such capabilities can yield. DoD writ large should go beyond the paltry level of effort of recent years and support additional cooperative programs and initiatives through service laboratories, DARPA and other DoD elements with the UK, Japan, Israel, and other close allies.

To be sure, there are other critical tasks needed to improve our defense acquisition outcomes, including the modernization of the Defense Production Act to deal with 21st century military contingencies, pandemics and other crises and a fresh examination of other ways to to ensure a robust and competitive defense industrial base to meet our national security needs. All of these steps require a deeper DoD engagement with industry to drive change.

In sum, with these types of hands-on measures, there is a chance that the new DoD acquisition leadership can move the needle and produce acquisition outcomes that can make a difference in real time. Department leadership on a “non-acting” basis and the clear direction it can generate is vitally important in this area – not to dictate, but to learn and shared across the enterprise entrusted with our national defense.

Jeff Bialos is a Washington, DC.-based partner in Eversheds-Sutherland LLP, a global law firm. Bialos served as deputy undersecretary of defense for industrial affairs during the Clinton Administration.

As Pentagon awaits supplemental dollars, its operational funding is $2B in the hole

The House is teeing up a series of votes this weekend on separate supplemental spending bills for Israel, Taiwan and Ukraine.