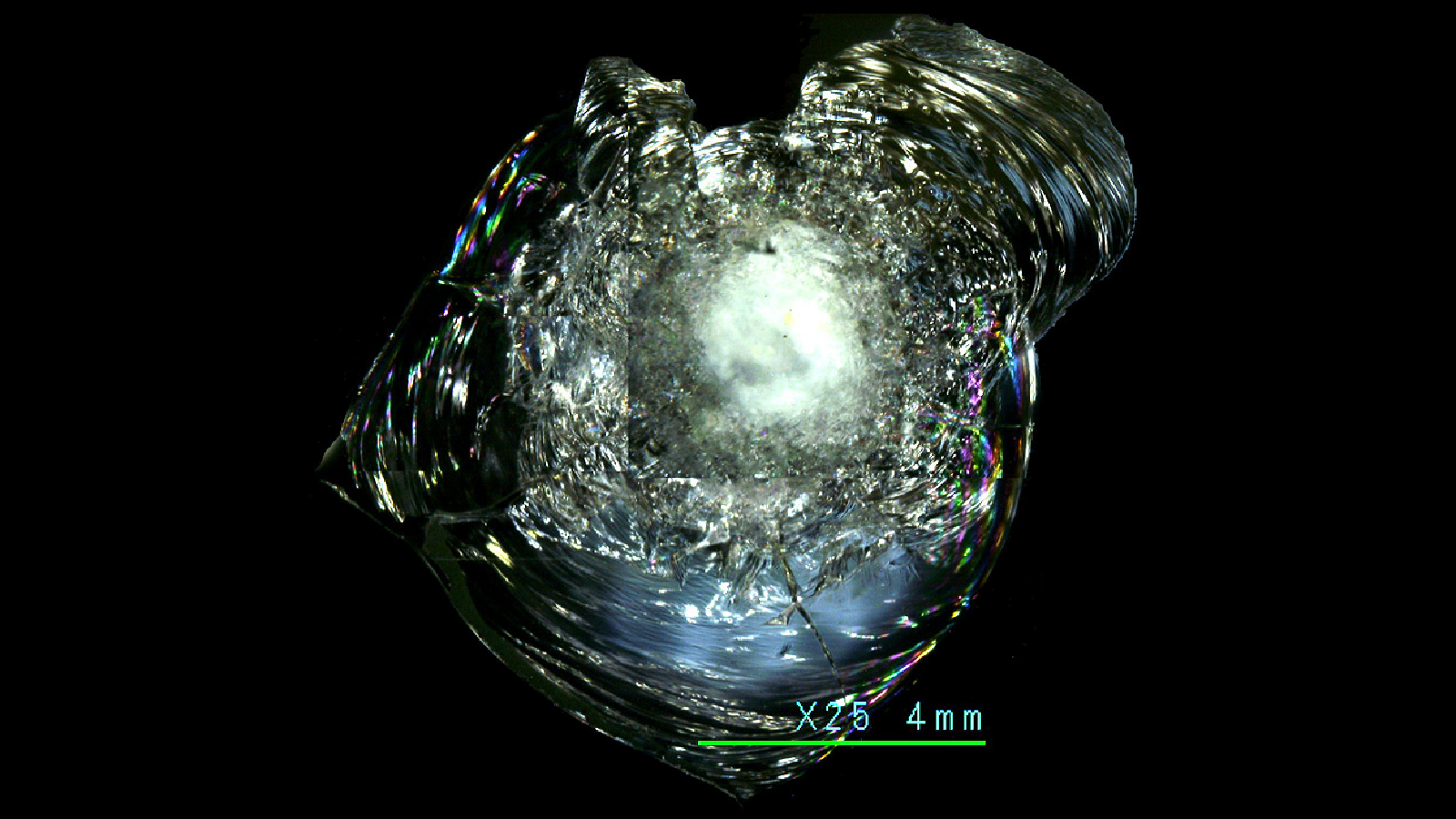

Picture of damage discovered on STS-126 Window No. 6. (Credit: NASA)

WASHINGTON: The Intelligence Community’s cutting-edge research arm is eyeing a new project aimed at detecting small but potentially deadly pieces of space junk that endanger satellites and astronauts, and is asking industry and academia for help.

The project is a bit off the beaten track for the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA), which, like its sister military agency DARPA, doesn’t have an operational mission; instead it is charged with early research on complex technology challenges. But the IC does have a dog in the fight to get a handle on ever-increasing amounts of space junk. After all, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) owns and operates the bulk of the nation’s spy satellites.

“The problem is continuing to get worse. And we’ve reached a point of no return … now we have a point where more debris is going to be created than actually returned to the Earth,” Alexis Truitt, IARPA’s program manager, told Breaking Defense.

“We invest in high-risk, high-payoff research to support some of the most difficult challenges to the IC,” she said. And debris is “one of the hardest challenges that is affecting satellites worldwide.”

IARPA’s Feb. 10 request for information (RFI) seeking ideas from industry and academia on novel methods to find and track small debris stems from the January 2021 National Orbital Debris Research and Development Plan [PDF], Truitt explained.

The Biden White House in November announced that it intended to update the plan, which called for research on limiting debris creation, tracking and characterizing it, and removing or repurposing it. And to that end, the Office of Science and Technology Policy last month began a round of consultations with industry, experts and researchers.

Specifically, IARPA is focusing on finding space junk between 10 centimeters and one millimeter in diameter, which currently eludes the tracking capabilities of Space Command’s 18th Space Control Squadron and commercial firms providing space situational awareness services. This would fill a gap that currently no other federal agency is working on — Space Force is focusing on ways to better characterize debris to achieve what officials call space domain awareness; and NASA has for a number of years been targeting teeny millimeter-sized debris.

The RFI asks interested vendors and university researchers to respond by March 11 with information on “existing or newly proposed technology for ground, air, and/or space sensors,” ranging from commonly used optical cameras and radar to more exotic sensor capabilities like solar sails and the signals from global navigation satellite systems.

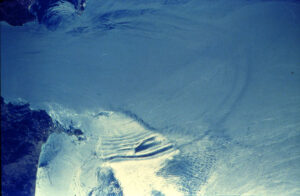

A soliton wave in the Straits of Gibraltar. (NASA photo)

It also asks for information on “pertinent physical phenomena including but not limited to plasma density solitary waves (solitons), electrostatic discharge, orbital decay, magnetic field perturbations, and/or radio wave emissions produced as the orbital debris interacts with the surrounding plasma environment.”

In particular, the RFI explains “there is reason to believe that debris-induced solitons offer opportunities for detection and tracking.”

Truitt, who has a background at NASA and in plasma physics, explained that solitons are unique waves that can appear in any fluid, and that their behavior in space is similar to their behavior in water.

If you imagine watching the waves at a beach, the solitons are the waves that appear to skim across the surface, maintaining their shape as they travel, as opposed to the waves whose shape and size change over time as they approach the shore. Scientists can use the unique profile of a soliton to help characterize the object that created it.

The RFI also seeks information on “specialized sensor collection modes” and “probabilistic detection techniques for low signal to noise objects,” as well as ways to improve and speed data characterization.

“We want to certainly survey the state of the art, across industry and academia and even international partners,” Truitt said. “We are planning to host a workshop this spring and will have finished reviewing the RFI responses by that time.”

European Space Agency debris impact test showing results of a 1cm metal ‘BB’ into a piece of aluminum. (ESA photo)

IARPA doesn’t talk about its research budget. At the same time, the agency touts itself as funding research that companies and university researchers would not otherwise be able to pursue, either because the work is too risky or lies too far ahead on the horizon.

The IC research arm always aims to find transition partners with funds to take its research into a formal research program of record, in the same way as DARPA.

“Traditionally, our primary transition partners are the IC and DoD,” Truitt said. “And orbital debris is a great risk to our mission sets here. But there could be an additional advantage for other agencies to benefit from this research. And we will be working closely with those other agencies, if we pursue an orbital debris program.”

‘Changes’ expected in ISR satellite operations to sort NGA, Space Force roles: White House official

“In the end, what we’re really going to have to figure out here is: what needs to change? Is it policies? Is it authorities? Is it processes? Is it funding? Is it purely just advocacy and communication?” said National Space Council Director Chirag Parikh.