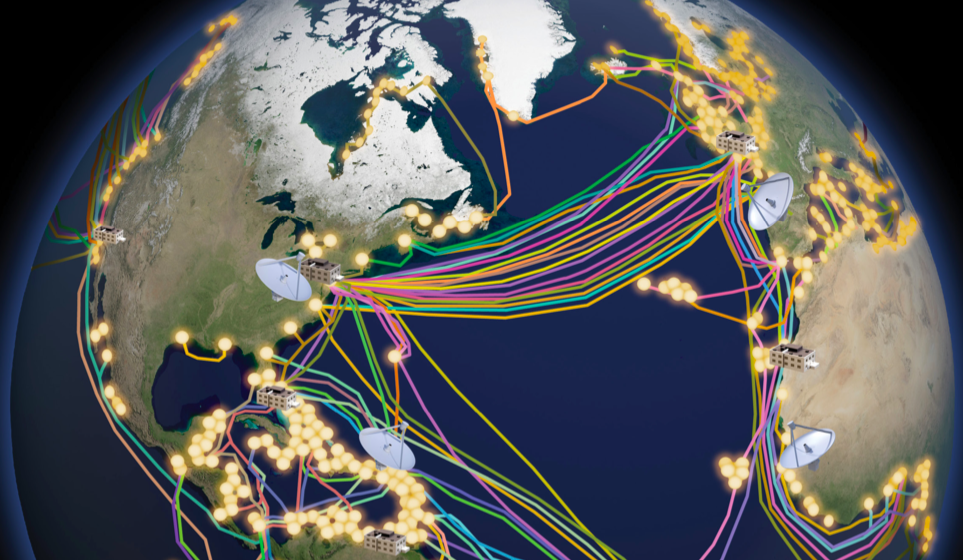

Undersea cables carry the bulk of intercontinental internet traffic that underpins global economic activity. (Aerospace image)

WASHINGTON: Some 430 undersea fiber optic cables carry 99% of intercontinental internet traffic, and those lifelines of global commerce are highly vulnerable to natural — and increasingly deliberate — disruption, a new study by Aerospace Corporation’s Center for Space Policy and Strategy warns.

“Undersea cable infrastructure is ripe for sabotage,” said Karen Jones, one of the authors of the study. She spoke to Breaking Defense news along with co-author Lori Gordon in an interview Wednesday.

The study, “Global Communications Infrastructure: Undersea and Beyond,” concludes that while the US should increase protection efforts, it also needs to look at how other types of communications infrastructure can be utilized and protected to provide alternate pathways for this traffic.

“Government and industry should continue to secure the communications enterprise—including undersea, terrestrial, air, and satellite segments,” the study states.

In particular, the study finds that new, high-capacity broadband satellites could provide backup for undersea cable infrastructure (UCI). These include the emerging mega-constellations in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) such as SpaceX’s Starlink and Amazon’s Project Kuiper.

“Although UCI will continue to offer unrivaled backbone capacity for years to come, space-based solutions … will offer alternate secure data paths,” the study says. Aerospace Corporation is a non-profit federally funded research and development center that advises the US government on aerospace policy issues, and pioneers technology solutions.

The study also suggests that the US consider working with the international community to develop norms of behavior around best practices and against damaging cables as they cross the high seas, as well as working with allies and partners to beef up best practices to secure facilities and enhance resilience, and to share information on threats.

Gordon stressed that the key takeaway from their in-depth study is that US needs to bring together all the different communications sectors that up to now have functioned primarily in stovepipes in order to both secure UCI and establish resilient hybrid networks. This includes supporting the development of emerging technologies.

For example, she noted, the Pentagon’s Space Development Agency (SDA) already is playing a key role with its effort to build a data transport layer for military communications in LEO to augment current Pentagon satellites. As part of that effort, it is investing in the development of optical inter-satellite links that are crucial for LEO-based megaconstellations to function.

Natural vulnerabilities to UCI abound, from storms and tsunamis to climate change that is changing the coastlines where cables emerge to link up to either satellite communications networks or cell towers. But Jones listed three reasons why nations should be increasingly worried about possible sabotage of UCI.

“One, it’s very easy. They span thousands of miles, they’re not guarded,” Jones explained. “You can get down there if you want to create mischief. You can go down in a mini-submarine which you can easily hide in a mothership, and go down there with hydraulic shears and cut the cable, or possibly tap into a relay or repeater station.”

Secondly, “the impact is severe: national economies depend upon these undersea cables,” she said. For example, she cited the paper’s finding that the US Clearing House for Interbank Payment Systems, know as CHIPS and familiar to anyone who has worked overseas for a US company, does some $1.8 trillion in monetary transactions among 22 countries every single day.

And the third thing is that “bad actors can enjoy plausible deniability.”

The issue of potential sabotage was highlighted last month with reports that amidst the heightening tensions with Russia over Ukraine, one of the two cables owned by Space Norway linking mainland Norway to the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean — which houses a primary ground station for links to polar-crossing comsats satellites — had gone dark. While the cause of the damage has yet to be officially announced and a fix has been found to restore functionality, there has been rampant speculation that Moscow was sending a shot across the bow.

Meanwhile, Ireland’s military is concerned about a planned Russian naval exercise near its territorial waters in the vicinity of cables that link Europe to North America, according to an analysis published Monday by Atlantic Council non-resident fellow Justin Sherman. This would not be without reason: in February 2020, British and Irish media reported Russia’s spy agency had sent agents to “inspect” the 13 cables that land in Ireland, and discussed fears that the cables may have been tapped to allow Moscow to exfiltrate data.

US postured to lose without a Standing Combined Joint Task Force in INDOPACOM

In this op-ed, John D. Rosenberger discusses the need for a Standing Combined Joint Task Force to face the China threat.